Trip Report: North Sister (May 31, 2014)

This is a few months old now, but I think it’s still worth posting about.

In an effort to train for our upcoming trip to the Tien Shan mountains in Kyrgyzstan, my roommate, Dylan, and I have been planning out climbs on some of the more technically challenging Cascade volcanoes. Of course none of them can prepare us for the altitude, but that wouldn’t last anyway. Mainly we want to get some experience with technical climbing in the mountains, as most of our climbing experience is bouldering, sport, and small trad routes. Between us we have effectively zero practical experience with technical alpine climbing, but that needs to change soon, and fast.

We thought North Sister, out near Bend, might be a good place to start because its standard route is apparently considered the most challenging of the standard routes in the Oregon Cascades. Also, it doesn’t involve any mandatory glacier travel.

We watched the weather during the week leading up to the trip, and it wasn’t looking promising. The NOAA forecast predicted a chance of thunderstorms, and the overnight low temperatures were barely going to get down to freezing. We were ready to call off the plan until the day of, when we made the last minute call to at least drive out and see for ourselves what the conditions were like.

We stopped by Backcountry Gear on the way out of town to grab some alpine gear. We picked up two small snow pickets, one big snow picket, a snow fluke, and an ice screw. Unfortunately we only had one 60m non-dry rope, which we knew would be less than ideal, but neither of us was ready to drop a few hundred bucks on a set of dry treated half ropes.

We left Eugene mid afternoon and got to the trail head around 6pm, less than ideal considering how far in we were hoping to make it to set up camp. The trail was really easy to follow. It goes more or less straight most of the way. It cuts across the width of the Pole Creek Fire burn. The beginning of the hike is really surreal because of it. There is literally nothing left alive in most of that area. The soil has been burned to dust and there is not a sign of any regrowth in the middle of it. Towards the edge of the burn area there is regrowth working its way in, but you can really see the effects of decades of fire suppression in that area; most of it is just completely dead.

Once we made it past the burn a ways we started hitting patches of snow. It wasn’t long before we completely lost the trail and started route finding based on what short glimpses of North sister we could get. The hike from there to camp did have a few spectacular views of the sisters, and of the North side of Broken Top. We were determined to make it past tree line before camping, which turns out to be a pretty big hike when you get a 6pm start, but we finally made it to the South-East flank of the mountain just past treeline just before dusk.

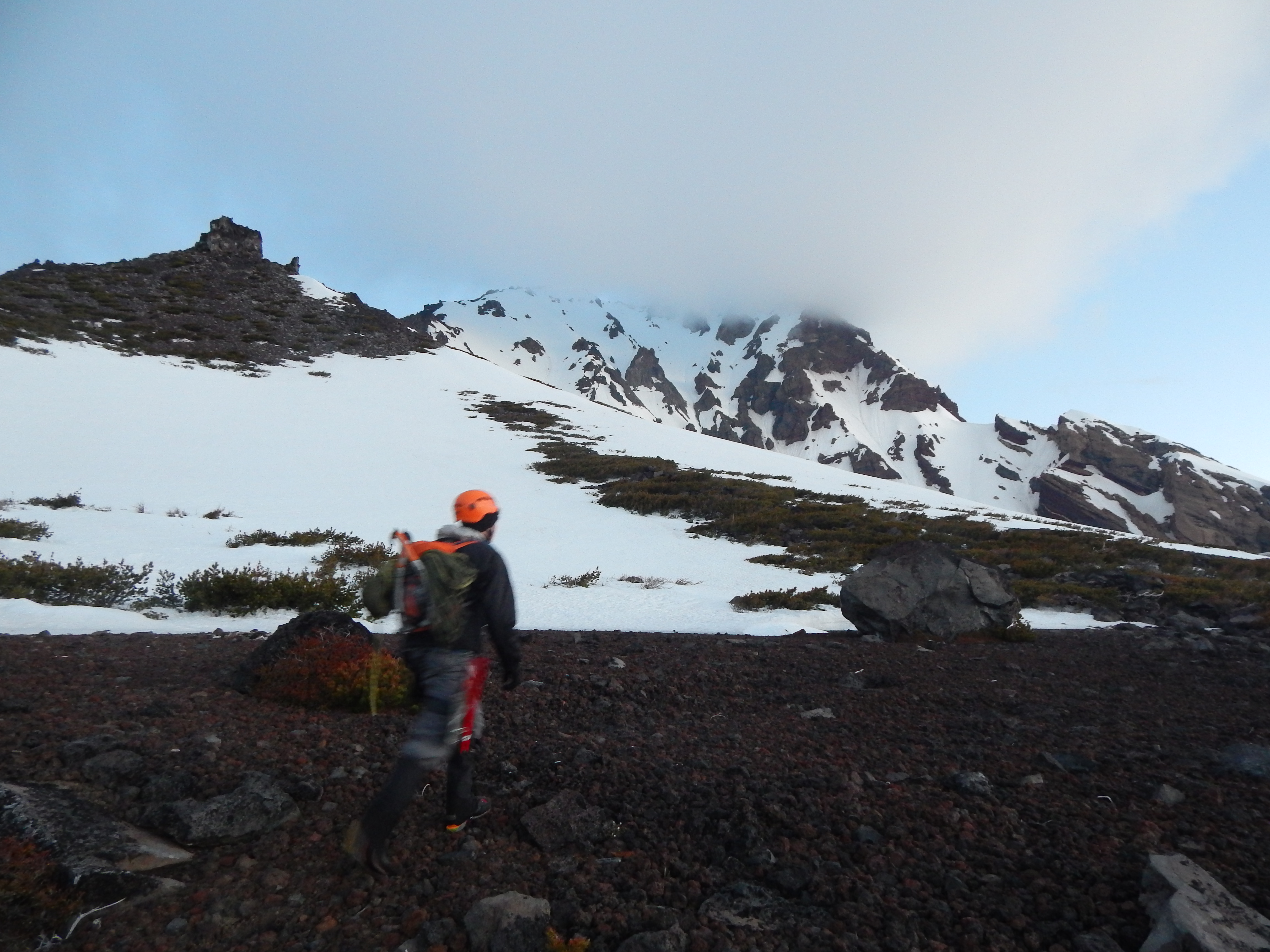

The next morning we got up around 3:30am and were hiking by 4. We started out the day with a classic Dylan moment. He was trying to figure out a way to carry the big snow picket that would be stable and not awkward, by wedging it sideways between his pack and his back. At the top of the first hill we hiked up, the picket slipped out and skated on the snow all the way back to the bottom. He ran all the way down after it but wasn’t able to find it. We had left the ice screw at camp so we went the rest of the way with two small snow pickets, and a fluke.

The hike felt long, mostly because of the endless scree you find on all of the Cascade volcanoes. North sister is made of particularly chossy rock, which makes the situation extra bad. In some ways it’s surprising that the mountain is standing at all. The whole mountain is basically just a pile of gravel at the angle of repose. It seems to be precariously held in place by a series of slightly more competent dikes[1]. Hiking gets easier once you’re high enough to travel on only snow, which was relatively high on the mountain by late May.

We hiked up the Southeast ridge to the summit pinnacle. Route finding was was easy through this section, except one point where we missed an obvious path over a gendarme and traversed some steep snow below it instead.

The summit pinnacle is the only technically challenging part of the climb. It starts with a section called “The Terrible Traverse” which didn’t quite live up to its name, but is certainly more difficult than anything lower on the mountain. The snow was getting soft by the time we got to it and I almost called off the whole thing at that point except that there were still a ton of people heading out on the traverse which gave me hope that we weren’t too ridiculously late. We roped up and pitched out the terrible traverse (with some simul climbing) on our now-soaking-wet 60m sport climbing rope. That was a hassle, and we moved slowly, but I think we were pretty efficient in general. The traverse its self is just a steep snow slope. Crampons and two ice tools were good to have, but there wasn’t anything technical, and no solid ice to speak of. The only thing that made the terrible traverse nerve racking was the constant rock fall from the summit pinnacle. The mountain is actively trying to self destruct.

The last pitch of the climb is, aptly, named “The Bowling Alley” because of the constant rock and ice cascading down from the true summit. Fortunately, the climbing route is actually pretty much free of rock fall, the real show is going on about fifteen feet to your left. The climb is a short pitch of 70 degree alpine ice through a chute on the Northwest side of the summit pinnacle. This is the section where I really wished we had brought the ice screw. Dylan belayed me on an anchor made of one small picket and both of his ice tools. I placed the other picket low on the pitch, before I hit the solid ice. Then I effectively soloed the rest of the pitch, with the added risk of dragging Dylan down the mountain with me in the case of a fall. Fortunately the climbing isn’t technically very difficult, but the exposure freaked me out a bit. I mostly just tried to not think about it.

Somebody graciously left a fixed webbing sling at the top of the pitch which I clipped in to as soon as I was close enough to reach it and belayed Dylan from there. There’s about 25 feet to the end of the real climbing, which we belayed as another very short pitch. We could have easily linked the two pitches with the 60m rope but I knew I wouldn’t be able to build an anchor that solid at the top with just the snow fluke so I chose to belay Dylan through the difficult stuff from the sling.

We were on the summit at about 12-12:30. Good views, nice weather.

The descent was actually harder than the ascent in many ways. We were a little burned out, and without double ropes, we couldn’t rappel through the whole bowling alley. We basically down-lead climbed to the anchor, rappelled the main ice section, and down-lead climbed the lower snow part. Then we pitched out the terrible traverse, the same way we came across it in the morning. It took a long time, and by the time we were done the snow conditions had gotten pretty bad. The rock fall had increased as it had warmed up, and the sun was almost on the traverse so the snow was getting mushy. I didn’t check the time, but I’d say we were back to the beginning of the terrible traverse by about 1:30 or so. It’s not much distance, but we were moving pretty slow.

Hiking out was a bit of a chore, too. Dylan was really crashing because he decided to eat all his food before we even got to the terrible traverse. We made it back down to camp by about 4 and packed up all of our stuff.

The rest of the hike out was uneventful, but felt long. We got back to the car after dark, around 27 hours after we started, with about 3.5 hours of sleep under our belts and a lot of walking. But it was good to be back and I was actually feeling very awake. I bought a ton of candy bars and chips at the gas station in Sisters and drove back to Eugene. By the time we got home we were both pretty burned out.

Our roommate, Ben, didn’t believe that we had taken over 24 hours to climb just one mountain and was convinced that we had sneakily linked up Middle Sister too. He was pretty bitter that he hadn’t gotten to join. I don’t think he would have enjoyed it.

[1] Mariek E. Schmidt, and Anita L. Grunder. “The evolution of North Sister: A volcano shaped by extension and ice in the central Oregon Cascade Arc.” Geological Society of America Bulletin 121.5-6 (2009): 643-662.